Image Warping and Mosaicing

Recovering Homographies

After taking my pictures, I manually marked correspondences in my images between two views. I also manually marked corners on the images corresponding to the extent of the images to include in my mosaic. Using these pairs of correspondences, I could recover the Homography matrix satisfying the relationship \(p'=\matrix{H}p\), where the homography matrix H has 8 degrees of freedom. Since each point pair gives us two equations, we need at least \(4\) correspondence pairs to solve for our homography matrix. However, if we can provide more, we can end up with a more robust solution by solving a least squares problem. Our homography matrix is a \(3 \times 3\) matrix of the form: \[ H = \begin{bmatrix} a & b & c \\ d & e & f \\ g & h & 1 \end{bmatrix} \] Flattening out this matrix and setting up the system of equations by plugging in our correspondence points, we get the following system of equations we can solve by Least Squares: \[ \begin{bmatrix} x_1 & y_1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -x_1x_1' & -y_1x_1' \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & x_1 & y_1 & 1 & -x_1y_1' & -y_1y_1' \\ x_2 & y_2 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -x_2x_2' & -y_2x_2' \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & x_2 & y_2 & 1 & -x_2y_2' & -y_2y_2' \\ & & & & \vdots & & & \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} a \\ b \\ c \\ d \\ e \\ f \\ g \\ h \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} x_1' \\ y_1' \\ x_2' \\ y_2' \\ \vdots \end{bmatrix} \]

Image Warping and Rectification

Now that we have a homography matrix between two sets of correspondence points, we can use this matrix to warp images into different perspectives.

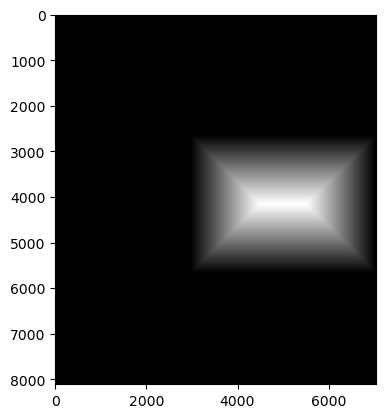

I used the homography matrix to first forward warp my defined corner points, and then I used an inverse warp on all of the points inside this defined region.

I used scipy.interpolate.RegularGridInterpolator to interpolate the original pixel values of these new warped points.

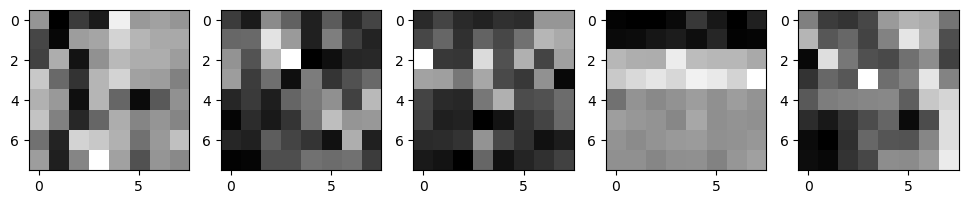

An interesting use of this homography matrix that also was a good test of its accuracy was to rectify images. I chose a rectangular portion of my images and then warped them to a rectangular shape (I arbitrarily chose a base and height dimension for my rectangles).

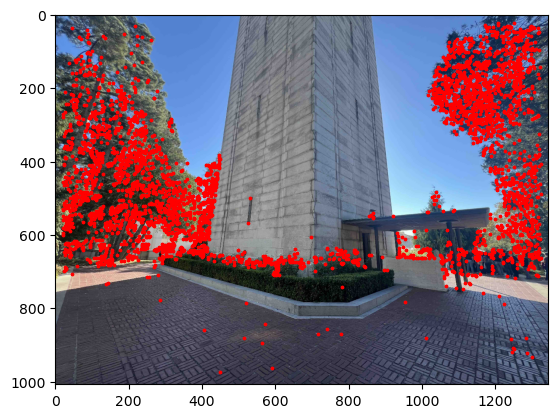

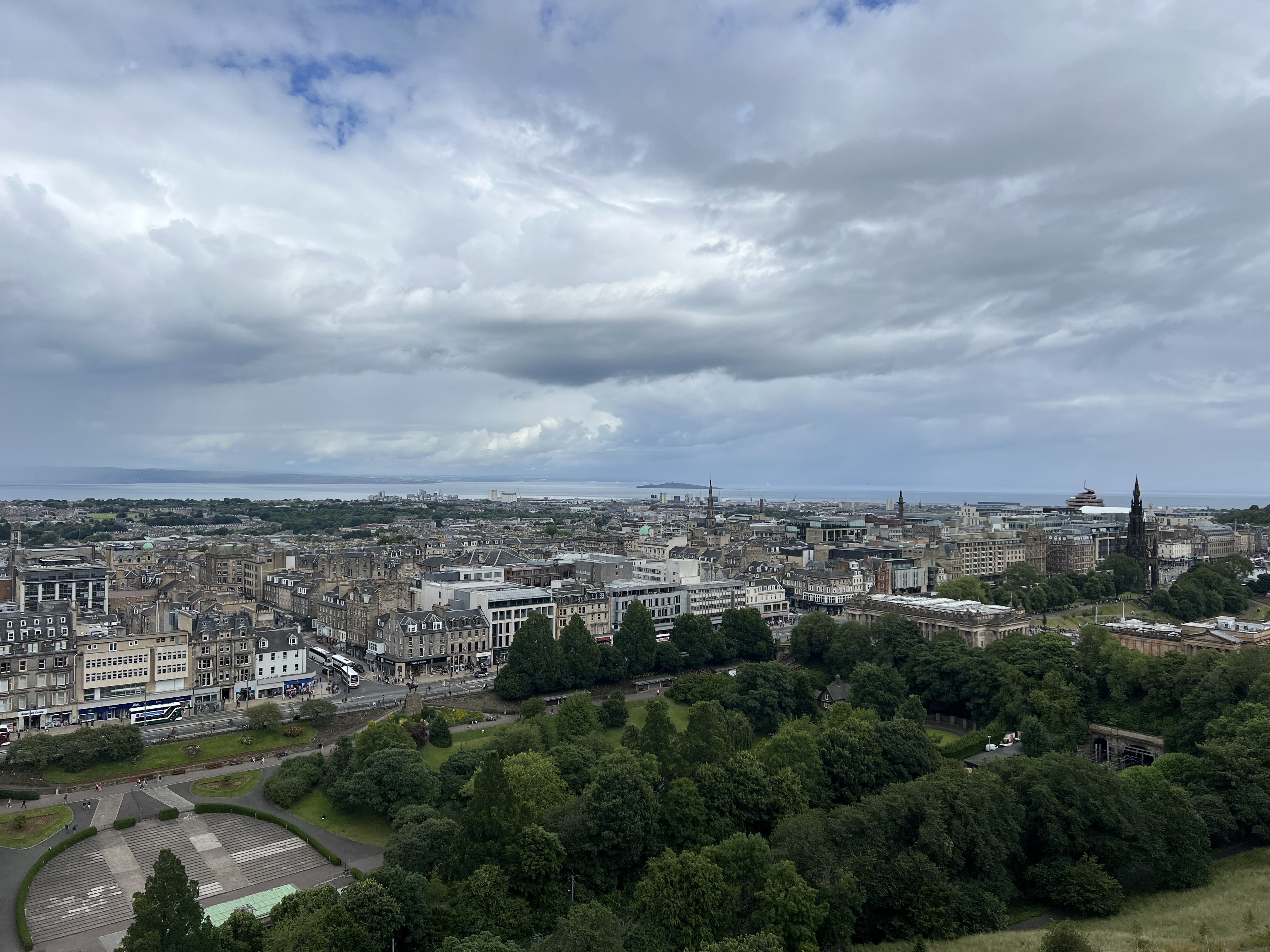

Rectification Results:

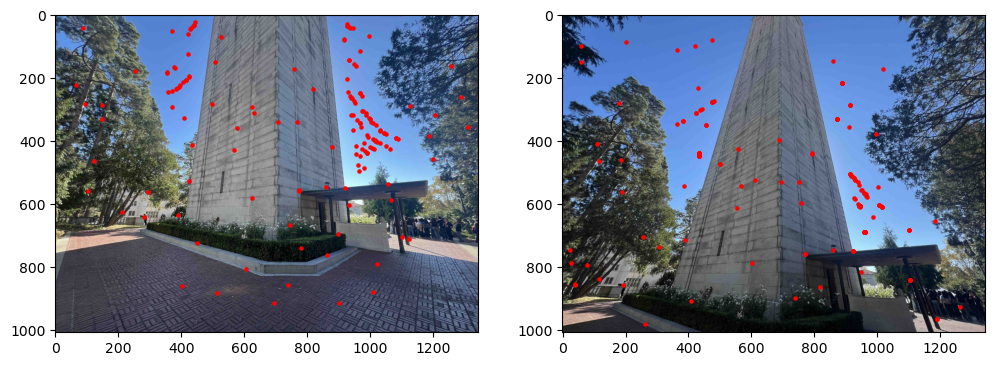

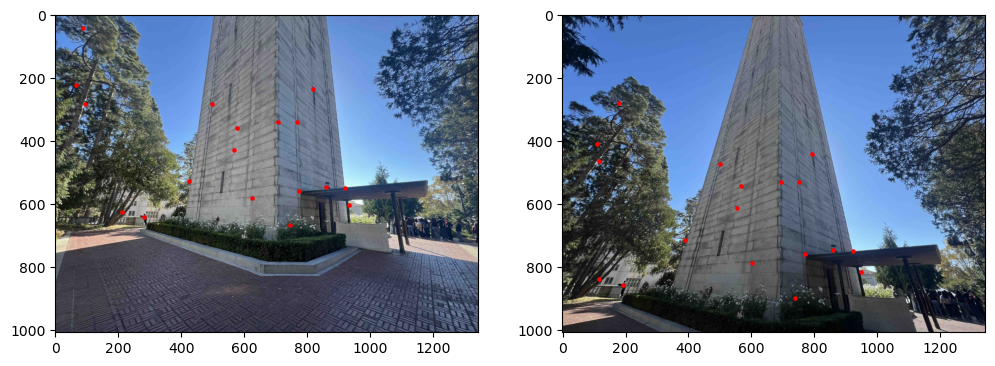

We can also use this same warping procedure to warp images into the same perspective to be used for image mosaics. Instead of warping to a rectangular region, we can warp correspondences from one image to another to get two images taken from different angles to be in the same perspective.

Image Mosaics

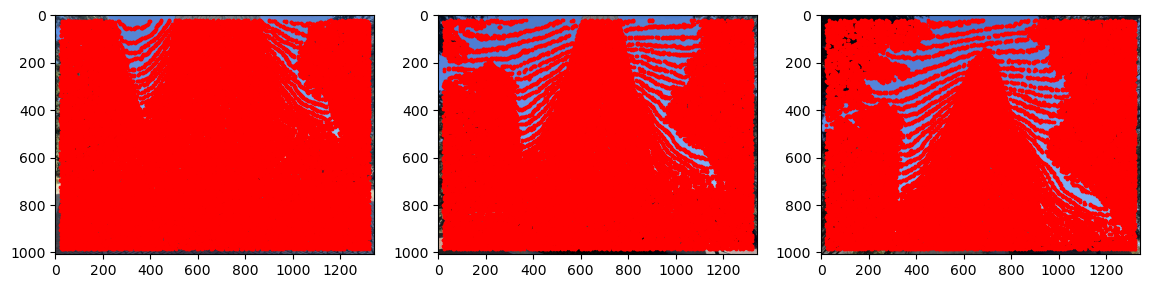

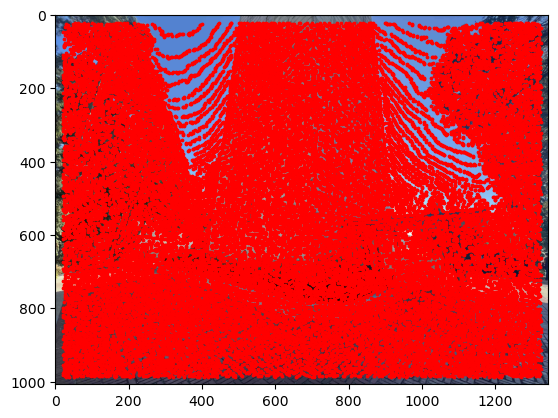

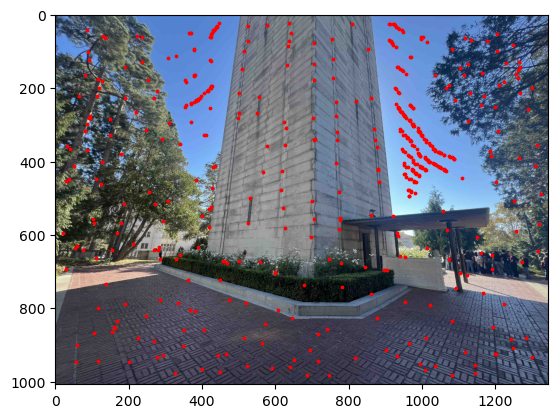

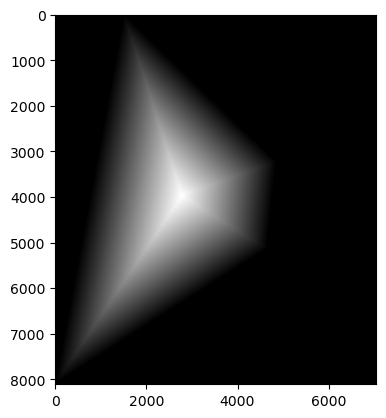

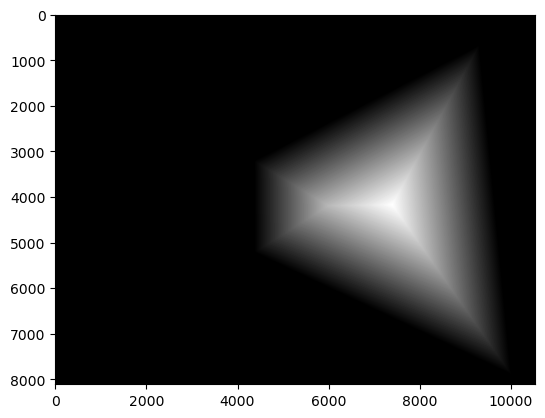

To convert my sets of images into image mosaics, I first had to warp all of the images into the same perspective using the method described in the previous section. I designated one "middle" image which all of the other images would be warped to. I then lined up the images according to the location of the correspondences of the middle image, and allocated space around to fit the other images. I then used a binary mask of the image shapes followed by a distance transform to construct a blending mask for the images. The distance transform represents the distance of each pixel to the nearest edge of the binary mask (I used Euclidean Distance). This could be considered as a representation of the "weight" of each pixel based on its distance from the "center" of the image.

I then used the distance transform to create the final blending mask I used by comparing the distance transforms of each image to create a binary mask. With this blending mask and the warped and aligned images, I could then blend the images together using a Laplacian Stack to create the final image mosaic. I ended up finding that when taking my pictures, I rotated quite a bit between perspectives, so this created a very warped image mosaic. This also made it slightly difficult to fully blend out the edges between the images (I also used images that were slightly too large, so the code would often crash my notebook kernel).

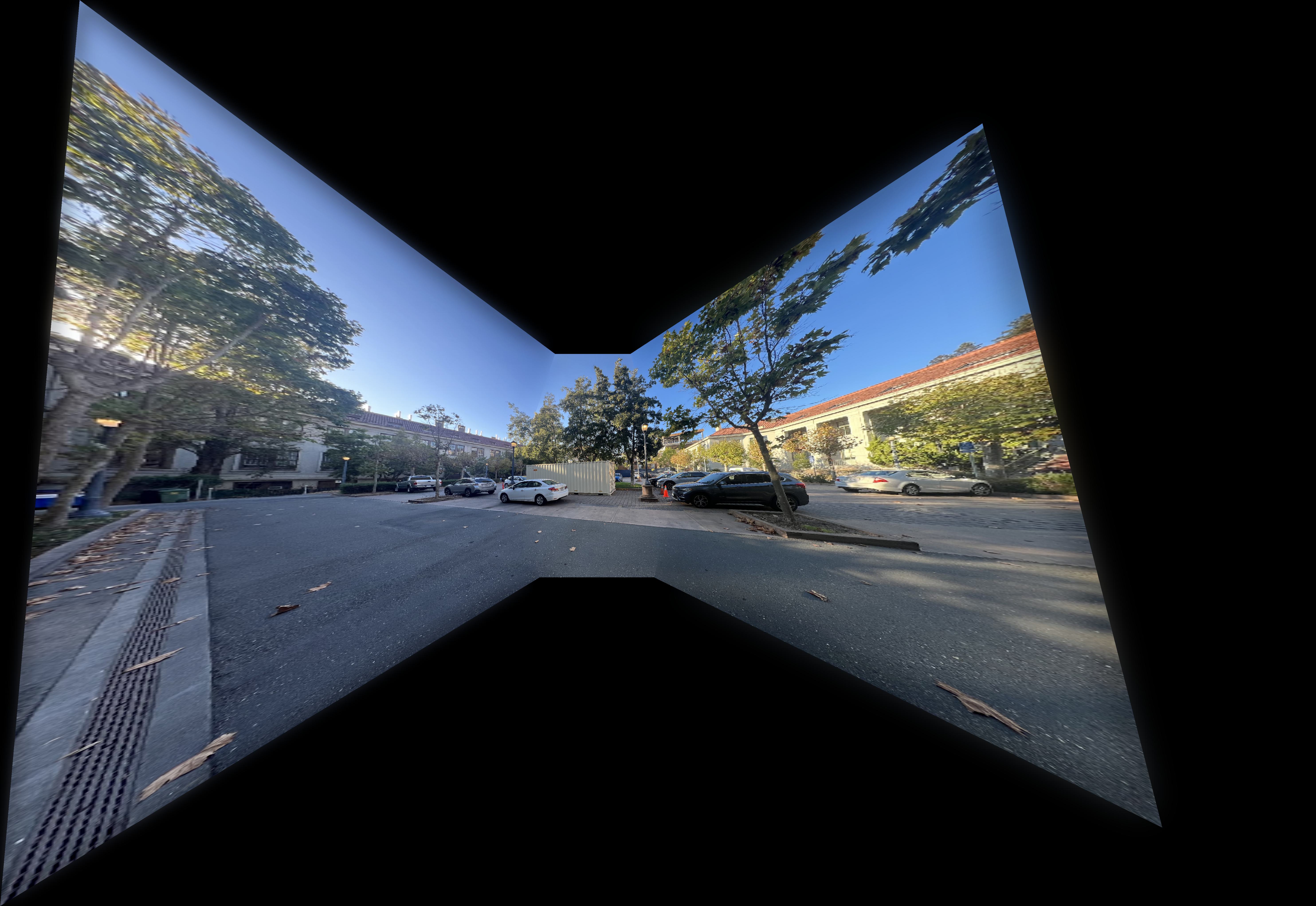

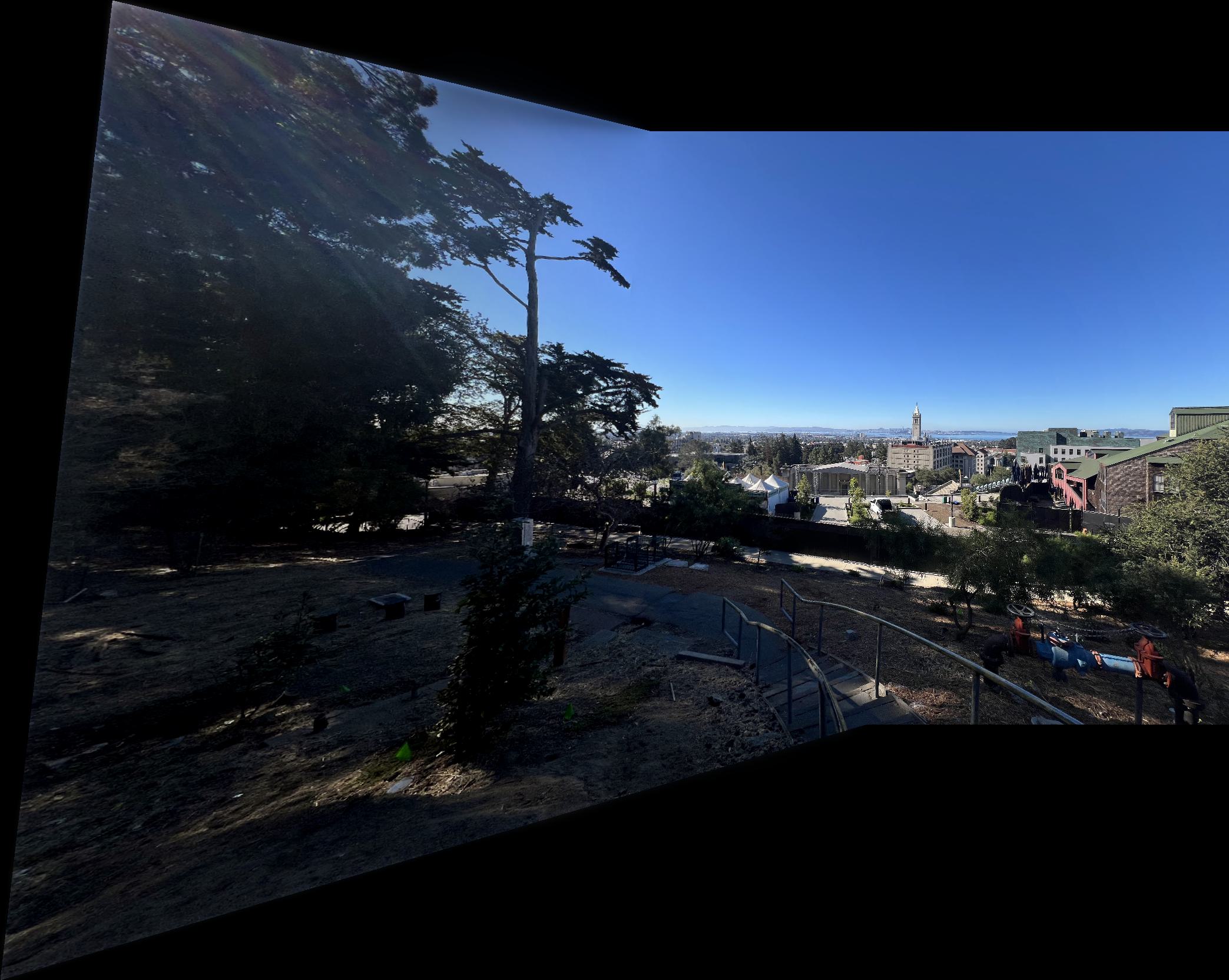

Image Mosaic Results: